Focus on Asia – Trade Tensions

Author: Dr. John Greenwood (Chief Economist)

Q1) What is your view on the potential impact (both positive and negative) of US-China trade tensions on Asia in general?

Dr Greenwood: The fallout from a trade war between China and the US may harm other Asian economies.

The biggest potential impact is on the economies of Taiwan, Korea and Malaysia. These economies sell goods to China that are used to make products exported to the United States, from automobiles to consumer electronics. Tech components such as computer chips are among the products most vulnerable to a trade war. Taiwan is in a potentially vulnerable position if the US-China dispute intensifies. Taiwan is a big supplier of components to the Chinese mobile phone and tech manufacturers. Much of this production is for the US market. In total, these exports make up almost 2% of Taiwanese GDP. But until the targeted goods are known exactly, it's difficult to quantify the actual impact on Asian economies. In fact, the damage could also be smaller than expected since China is the dominant supplier of many goods that it sells to the US. Also, US consumers may struggle to find sufficient substitutes to replace the goods that they currently buy from China, at least in the short-term. What's more, to the degree other Asian economies may be able to offer substitutes for Chinese products to the US market, some Asian exporters could benefit from any switch in US demand away from Chinese products.

Q2) In particular, do you expect Asian central banks to delay rate hikes as global trade friction intensifies. If that’s the case, could this cause capital outflow from Asia as the US continues rate normalization?

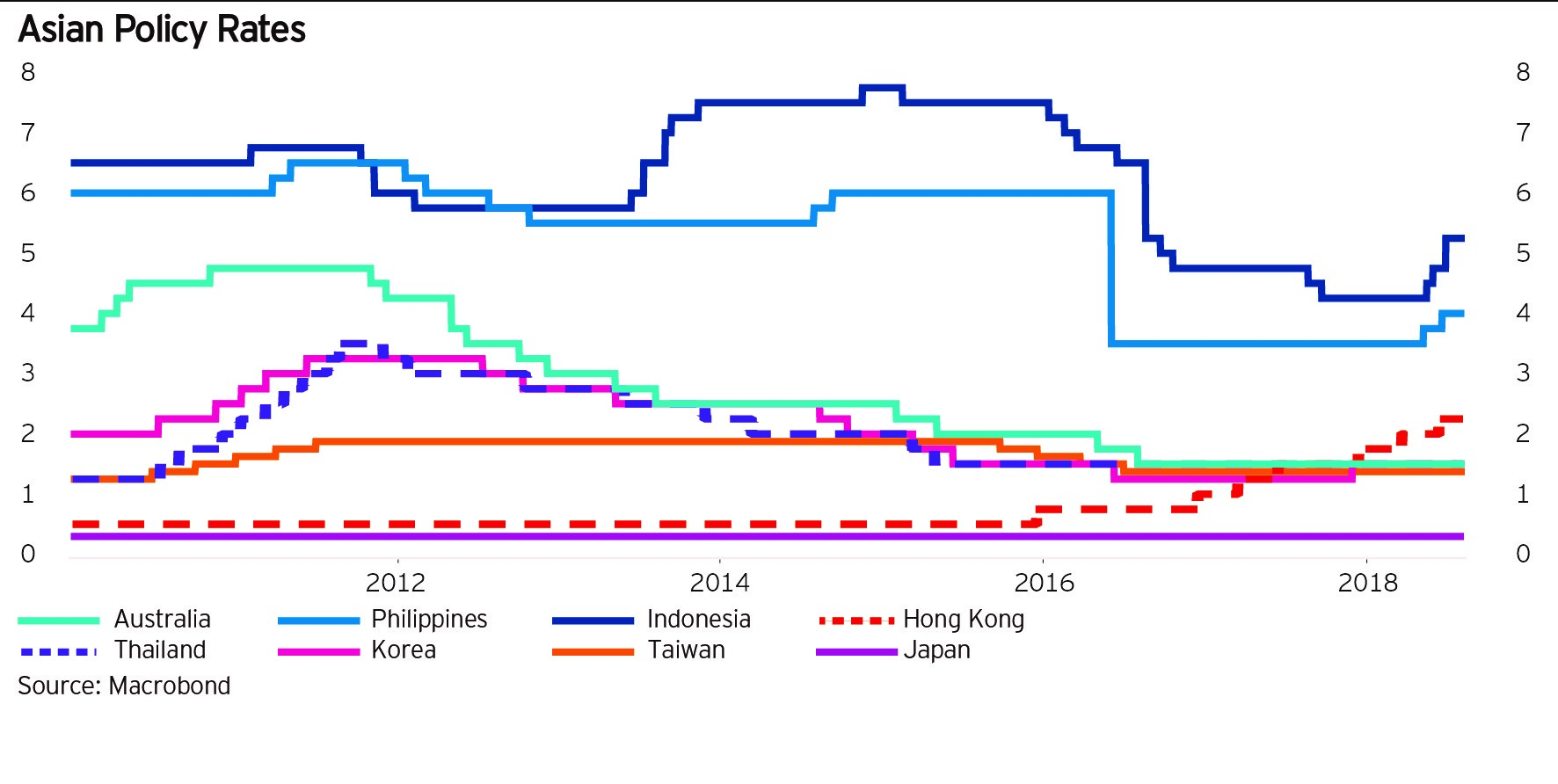

Dr Greenwood: Due to the slow rate of monetary growth in Asian economies, relative to their historic rates and potential growth, there is little domestic inflation pressure that would require Asian central bankers to raise rates. However, Asian economies with current account deficits will come under pressure to raise rates as the US Federal Reserve normalizes rates. Most exposed is Indonesia which has raised rates to defend the fragile Rupiah. Malaysia and the Philippines have also raised rates earlier in the year. Economies with current account surpluses such as South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand will not feel as much urgency to raise rates and will be prepared to allow their currencies to depreciate to remain competitive in the face of US import tariffs. However, economies such as Indonesia and Malaysia may face a dilemma – whether to delay raising rates due to slower trade growth or whether to allow their currencies to weaken more, risking (temporarily) higher inflation. Essentially, a strong balance of payments and a low inflation rate are the best defences against a trade war. Conversely, those economies with a weaker balance of payments or a risk of rising inflation will be the most vulnerable.

Q3) If, on the other hand, Asian central banks raise rates to stem capital outflow, could Asian corporations stand higher borrowing costs (as they have enjoyed low interest rates for several years), especially amid uncertainties on trade tensions?

Dr Greenwood: High borrowing costs would only become a problem if interest rates were to rise substantially from their current, historically low levels, but that is unlikely to happen anytime soon given the benign outlook for inflation. Prior to the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis many Asian economies maintained fixed exchange rates. Many Asian businesses had borrowed low interest dollars to finance their domestic business where their costs and revenues were in local currency. The boom in spending in the 1990s led to high inflation and high interest rates. When Asian currencies were devalued in 1997 and 1998 and the US dollar appreciated, debt repayment suddenly became even more expensive, imposing severe pressure and producing widespread bankruptcies. Since that time most Asian economies have moved to floating exchange rates, giving them much more of a shock absorber, and also inducing business borrowers to take less currency risk with their borrowings. Asian banks have also reduced their maturity mismatch – i.e. allowing customers to use short-term loans to finance long-term investments. Governments have also built up much larger dollar reserves. In summary, the risks are much less severe in the current environment.

Q4) At the center of trade tensions, China’s exports are set to be hit directly. Do you foresee this will bring opportunities for a structural change in the Chinese economy? What is your outlook?

Dr Greenwood: I do not envisage a major shift in China’s industrial policy. The Chinese government already aimed to cut excess capacity in heavy industry and boost consumer spending (i.e. to shift the composition of GDP to more consumer spending and less fixed asset investment). In addition, although the Chinese government already had in place the “Made in China 2025” program, this may be affected by the imposition of stricter US foreign investment rules. For example, Chinese companies may find it harder to acquire technology and expertise. But the China 2025 policy itself will likely remain even if its implementation becomes more difficult.

Some analysts have argued that the trade dispute may provide an opportunity for China to implement greater exchange rate flexibility, even moving towards a free float of the currency. In my view, this is a misconception. Although the yuan has depreciated over 5% against the dollar since the start of the year, it is highly unlikely that the authorities will change their strategy of maintaining capital controls, and adjusting them to suit the circumstances -- a free float with continuously changing capital controls is not really a free float at all. It will remain a broadly managed exchange rate system.